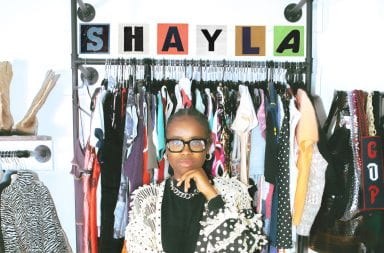

Star House, located at 1621 N. Fourth St., was founded by Natasha Slesnick in 2006 to act as a drop-in center for homeless youth in Columbus to feel safe and have basic needs met. Credit: Alaina Bartel / Lantern reporter

Many people have a moment that changes their life. For Natasha Slesnick, that moment was meeting a homeless youth. From then on, she knew what her life was going to be dedicated to.

“I was appalled,” Slesnick said. “I could not believe that we are one of the richest countries in the world, yet we have kids living on the streets who are hungry, who are scared, who are attacked, who are trading sex for a place to sleep or food or money, and I couldn’t tolerate this continuing to happen without doing something about it.”

Slesnick, a professor in Ohio State’s Department of Human Sciences, previously lived in Albuquerque, N.M., where she worked with homeless youth and created her first drop-in center, a place where homeless children and young adults can drop in and fulfill their basic needs.

She moved to Columbus in 2004 to continue working with homeless youth and noticed that there were no drop-in centers in Columbus for youth on the street to feel safe, which led to her founding Star House in 2006. The name “Star” stands for services, training, advocacy and research, Slesnick said.

Star House, which is located at 1621 N. Fourth St. and is open to individuals between the ages of 14 and 24, began as a research project Slesnick was working on to reintegrate youth into society. She would recruit homeless children and young adults to come to the house to help with research, but realized that they weren’t coming back.

“Because we weren’t a drop-in center, they wouldn’t return to work with their therapists and the counselors. So, we opened the house as a drop-in center to be open Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. in October 2006. It was when we did that that we were able to build relationships with the kids and start to build up trust,” Slesnick said.

Slesnick said she began to think about how victimized the youth must feel at night, and decided it was important for the house to be available 24/7.

After funding from the state of Ohio budget was approved for Star House in June 2013, the house was able to stay open 24/7 and also hired a therapist. Previously, when the house was open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., its budget was $150,000 a year, and that basically just allowed its doors to remain open. With the funding, the house was approved for $665,000 a year for two years, Slesnick said. The house also receives funding from the Ohio Attorney General’s office, and grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse, she said.

In addition to having a therapist, the house also provides services such as food, showers, hygiene items a telephone to make and receive calls, case management, job training and education, physical and mental health, and dental health. They can obtain their state IDs, and the youth can even use the house as their mailing address, said Denitza Bantchevska, director of the Star House.

Jeana Patterson, the program coordinator at the house, said that the drop-in center does not have any beds, because it is not a shelter. Instead, the people who work at the house will connect children and young adults who desire a shelter to the services they need.

Bantchevska said there are many levels on which they want to help these children, from engagement in the community to providing a space where they can feel safe and accepted.

“They are usually kids that are disconnected from the system. Many of them live in homeless camps, they couch surf with friends, they pick abandoned buildings, or a combination of the above,” Bantchevska said. “Typically, they do not receive any services, and they are disconnected from the system. Our goal is to connect them by building trust, and a relationship with them based on trust, and connecting them to services.”

Bantcheveska said youth homelessness is hard to see in Columbus, and the population is extremely marginalized. She said she thinks there are between 1,200 to 1,500 homeless youth in Central Ohio. The house served 724 children in 2014, and currently they see about 60 children per day, she added.

“There are many people in the community in Columbus who have no awareness of the existence of this problem,” Bantchevska said. “Youth homelessness is almost invisible. We barely see it on the streets (because) many of these young people mingle among the students or other young people in the community.”

Although the house sees mostly children from around Columbus, they are working to become a statewide center and eventually a national center, Slesnick said in a follow-up email.

“To my knowledge, we would be the only research-based center focused on youth homelessness in the country. And, we are currently the only research-based drop-in center in the country,” she said. “We are more than a drop-in center because we conduct research and also advocate and seek to change policy, and that’s what the move to a (statewide) house will solidify. That’s the goal, anyway.”

Slesnick said her favorite part about being involved with the homeless youth is trying to find a way to end their homeless life on the streets.

“By hosting interventions, I feel like I am getting one step closer to figuring out how we can really help these kids. So many times, people base policy decisions and funding decisions on interventions that don’t have any evidence base, and I feel like we really need to figure out what really works with these kids rather than keep doing things that don’t work,” she said. “What makes me really excited is really making progress towards figuring out what’s going to work to end homelessness.”

Although these children might be different in some ways, Slesnick said she believes that they yearn to have normal lives.

“They’re just kids,” she said. “They’re kids who want to be loved and want to have a chance to have a life like the rest of us have. Hopefully, people will be so moved as I was to come and do something about it.”