Upper left, clockwise: Aaron Lopez as Captain H, Patrick Wiabel as Red and Sarah Ware as Callie in a scene from ‘In Here Out There.’

Credit: Courtesy of Lesley Ferris

Since January, students in Ohio State’s Master of Fine Arts in Acting program have worked with autistic children in social skills training, inspiring the creation of “In Here Out There,” a play that opens Thursday.

The nine students collectively wrote the piece as part of the MFA Acting Outreach and Engagement Project, which is required in the program, said Lesley Ferris, interim chair of the Department of Theatre.

“A lot of people see autism as a disability,” said MFA acting student Aaron Lopez. “But this whole experience has taught me that it’s not a disability. It’s how they get through the world, which they view in this different and beautiful way that I’ll never know.”

“In Here Out There” delves into the life of Callie, a fictional 13-year-old autistic girl, whose fascination with superheroes leads her to frequently consult with two imaginary figures: Captain H, a personification of her courage and bravery, and Red, a personification of her fears and anxieties, said Lopez, who plays Captain H.

Click to enlarge.

“What’s great about Captain H is that I’m really Callie in some ways, because the character is a part of her inner-world,” Lopez said. “And Captain H is someone that she looks up to, and someone who often combats Red, the villain, to help her get through life.”

Before the graduate students engaged with autistic kids, the group went to London in 2013 to learn about the Hunter Heartbeat Method, a Shakespeare-based, social skills teaching intervention for autistic children, Lopez said.

“They then formed interesting, creative responses to the work with the children, whatever sort of sparked them,” said Maureen Ryan, director of the MFA Acting Outreach and Engagement project. “Sometimes (the actors) would come in with a scene based on what happened in class, and sometimes they just improvised.”

The effects of the Hunter Heartbeat Method were researched at OSU over the last two and a half years with collaboration between the Royal Shakespeare Company, Nationwide Children’s Hospital’s Autism Treatment Network, the Department of Theatre and the Nisonger Center, a university center that aims to improve the lives of those with developmental disabilities, said Marc J. Tassé, director of the Nisonger Center.

Kelly Hunter, English actress and developer of the Hunter Heartbeat Method, said she wanted to explore the power of Shakespeare outside of the theatre.

“The heart of the method is the iambic pentameter, the rhythm of the heartbeat, and the power that it has,” Hunter said. “Arguably it’s the first sound we hear in the womb, from our mother’s heartbeat. And what I’ve experienced is that this rhythm can genuinely calm children with autism, whose inner-rhythms are sometimes jangled or disturbed.

“Eventually I wanted to see if the method could be scientifically evaluated, but at the time there was no possibility of doing that in England,” she said, “And the RSC thought … ’Maybe there’s something OSU can do.’”

The two organizations have had an educational partnership since 2009.

Tassé said within the Hunter Heartbeat Method, children are given the opportunity to improve skills including voice, expression of emotion and social interactions, which are often lacking in autistic people.

“And in addition to teaching them much-needed social skills and communication skills, this method of intervention allows them to discover the arts, which can be a leisure or vocational interest for them,” Tassé said.

The Nisonger Center took questionnaires from parents of children that the MFA acting cohort worked with as well as a control group made up of children from Columbus City Schools, with results set to be published in spring 2015, Tassé said.

In London, the MFA actors heard directly from Hunter and were able to observe her as she worked with U.K. children, Lopez said.

From this, they learned a series of games centered on Shakespeare’s play, “The Tempest,” said Robin Post, director of the Shakespeare and Autism program for the Department of Theatre.

They then participated in local workshops once a week for two semesters at Haugland Learning Center — a Columbus school for developmentally disabled children — to observe and play roles from “The Tempest.”

Hunter has worked closely with about 65 children throughout the years, all of whom she chose to dedicate her new book to. Each child’s name is listed in the book, “Shakespeare’s Heartbeat: Drama games for children with autism,” which was released this month, Hunter said.

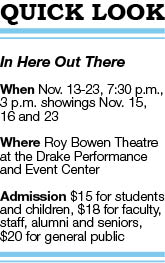

“In Here Out There” opens Thursday at 7:30 p.m. in the Roy Bowen Theatre at the Drake Performance and Event Center, and has nine additional shows throughout November, with the last taking place Nov. 23 at 3 p.m. A post-performance discussion will be held Nov. 15 with Hunter, Post, Tassé, the cast and others. Tickets are $15 for students and children, $18 for faculty, staff, alumni and seniors, and $20 for the general public.

The last showing is a little different. The “sensory friendly” performance will implement several technical changes in lighting, sounds, space and more to the theatre in order to accommodate autistic audience members, who can be sensitive to bright or flashing lights or events that require them to sit still, Post said.

Shakespeare’s work set a precedent in theater, and now it’s the heart of an emerging mode of teaching social skills to autistic children.

“In Shakespeare there are four key words that are repeated more than others, and they are ‘eyes,’ ‘mind’ ‘reason’ and ‘love,’” Hunter said. “So his plays are a poetic exploration of these words, which is brilliant for people with autism, because using their eyes and mind to find reason and love is the very thing they find difficult.”