[author image=”https://www.thelantern.com/files/2017/12/Copy-of-Erin-Gottsacker-1p5q674.jpg” ]Erin Gottsacker produced this story in her role as Patricia B. Miller Special Projects Editor.[/author]

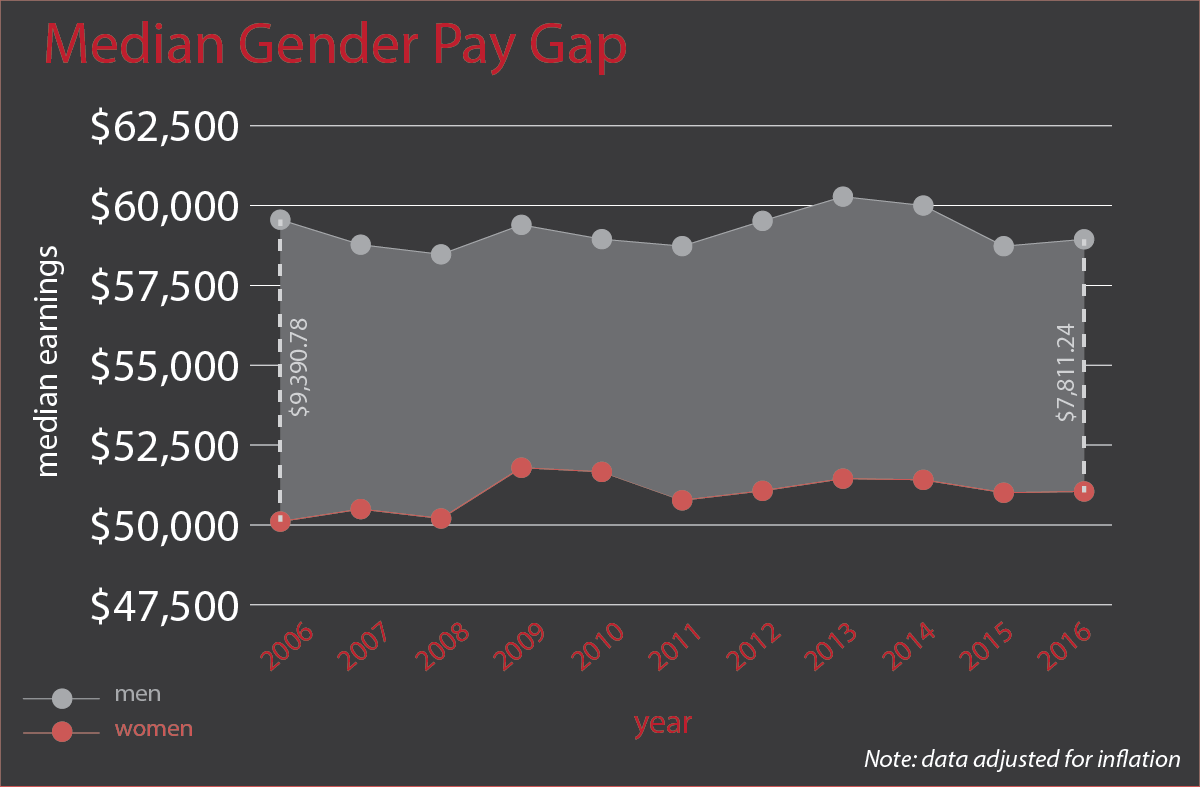

The gender pay gap has persisted across the decade at Ohio State, with male university employees earning about $7,811 more than female employees in 2016. Credit: Photo illustration by Ris Twigg | Assistant Photo Editor

They’re doctors and teachers, food service workers and groundskeepers, artists and scientists, office assistants and child care workers.

In nearly every profession and job category at Ohio State, women work side by side with men.

But they’re not paid equally.

An analysis of Ohio State payroll data covering thousands of employees and hundreds of job classifications found that men have consistently earned more than women in the past decade.

Last year alone, male Ohio State employees earned $7,811 more than females, when comparing all median salary values.

While that’s less than the $9,390 disparity in 2006, it confirms that Ohio State is not exempt from a problem that exists in nearly all industries across the United States: the gender pay gap.

“Higher education is supposed to be the vanguard of equality and equal opportunity. That’s not being reflected in the way [universities] treat their female employees,” said Jacqueline Bichsel, the director of research for the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources.

While the overall gap between men and women’s earnings appears to be narrowing, a deeper delve into the data reveals that in some job categories, wide disparities in pay haven’t only persisted across the decade — they have worsened.

The Lantern’s analysis of a decade of employee payroll information indicates that the difference in pay widens at higher rungs of the professional ladder, where, in addition to being paid less, women also are less represented.

When it comes to gender, we recognize that there is a gap. We also know that, unfortunately, this is a phenomenon that exists in broader society. We’re a part of that and we’re committed to addressing it. — Chris Davey, Ohio State spokesman

At the Wexner Medical Center, for example, the pay gap among physicians is substantially wider than the pay gap among patient-care associates. In academia, the wage discrepancy between male and female professors is greater compared with that of male and female assistant or associate professors.

Additionally, of the university’s 24 deans in 2016, five were women. That’s the same number of female deans as there were in 1999.

As the pay gap narrowed among full-time employees over the course of the decade, the gap in pay among part-time workers was three times higher in 2016 than it was in 2006.

Ohio State in April pledged to support a city of Columbus initiative to address pay inequality, “The Columbus Commitment: Achieving Pay Equity.” It is designed to encourage Columbus employers to collaborate in their efforts to empower women.

Before then, Ohio State did not have a system in place to consistently track the gender pay gap across the university’s various colleges and departments.

“We are very committed at Ohio State to addressing equity and to ensuring that we have a work environment where people are compensated fairly,” said Chris Davey, an Ohio State spokesman. “When it comes to gender, we recognize that there is a gap. We also know that, unfortunately, this is a phenomenon that exists in broader society. We’re a part of that and we’re committed to addressing it.”

The extent of the gender pay gap

Several months ago, The Lantern received salary data through a public-records request for every nonstudent university employee from 2006 to 2016, including information for employees of the Wexner Medical Center and branch campuses.

The data set included only information for regular employees, meaning it excluded 3,387 term employees, such as lecturers or post-doctoral researchers, and temporary employees, both of which are hired on a less-permanent basis.

In 2016, that data comprised 28,969 employees who earned vastly different annual salaries.

For example, Ohio State football coach Urban Meyer’s 2016 base salary was $818,640. That figure does not include incentives for his players’ athletic or academic performance or perks like a country club membership and car allowances.

Unsurprisingly, Meyer’s salary is not comparable to the salaries of most professors and medical center employees.

In 2016, only 12 of the university’s 100 highest-paid employees were women, while they made up 63 of the 100 lowest-paid employees. A decade earlier, 16 of the 100 highest-paid employees were women, while 81 of the lowest-paid employees were women.

To account for these outliers, The Lantern used the median — the salary point where half of employees earn more and half earn less — to calculate the gap in pay between male and female employees.

Additionally, the gender pay gap of full-time employees and the gender pay gap of part-time employees were separately analyzed, accounting for the impact that the number of hours worked has on pay.

The pay gap, which was adjusted for inflation in the analysis, narrowed among full-time workers, from $10,109 in 2006 to $7,188 in 2016.

I’ve been told, ‘You need more education.’ So I went and got that. I was told, ‘You need more experience.’ I went and did that. So everything you’re being told to do, you go and do. But yet you still don’t see the increase in your salary. — Shelly Martin, Patient Transport Manager, Wexner Medical Center

Among part-time workers, however, the gender pay gap widened from about $2,134 in 2006 to $6,608 in 2016, with a spike in men’s earnings in 2011.

These findings mirror pay gaps in different professions across the country, with full-time working men earning about 20 percent more than full-time working women, according to the American Association of University Women.

However, Kevin Miller, an AAUW senior researcher, said the gender pay gap as a percentage tends to be highest among well-compensated fields that require a significant amount of education.

Fields like medicine and academia, therefore, reflect a greater pay disparity than low-wage occupations, Miller said.

This observation holds true at Ohio State.

At the Wexner Medical Center

Last year at the Wexner Medical Center, 651 of the university’s 1,036 physicians were men, earning about $38,942 more than female physicians, which translates to male physicians making 24 percent more than their female counterparts.

That difference increases to $46,013 when comparing only physicians who work 20 hours each week. That accounts for 76 percent of the physicians at Ohio State.

A number of reasons contribute to this disparity, said Joanne McGoldrick, the associate vice president for total rewards within Ohio State’s Office of Human Resources.

Pay varies widely across different fields of medicine, she said, and physicians are paid differently depending on the amount of time they spend doing clinical work compared with conducting research or teaching.

However, the pay gap persists even when comparing male and female physicians who started working on the same day in the same area of medicine.

For example, two physicians in internal medicine, a man and a woman, both started working in July 1990. The woman is listed as a professor, while the man is listed as an associate professor. Despite the woman being of higher rank, the man earns about $20,000 more than the woman.

“There are a lot of factors that typically go into the pay aside from just their title,” McGoldrick said. “It’s also dependent on their years of experience and their curriculum vitae and the research grants they bring with them.”

This is not an isolated example, however. It occurs repeatedly among physicians who have been working with the university for several decades. Among more recent hires, that disparity is less prevalent.

“It’s very case by case. We do find some discrepancies [in pay], but I see them both ways,” said Brian Newcomb, the director of technology, process, and data solutions within Ohio State’s Office of Human Resources. “But why? We would need to dig into data that we don’t centrally hold today to see why that is. But we’re able to see a number of areas where that would be the next step.”

The gender pay gap also is less prevalent when examining jobs at lower levels of the medical center’s hierarchy.

For example, patient-care associates are charged with assisting nurses and tending to patients. Women make up 77 percent of employees in this position at Ohio State, with a median annual salary of $22,932 in 2016. Last year, those women earned slightly more than men in the same position.

Shelly Martin started working for the Wexner Medical Center as a patient-care associate in 1998 and has worked her way up to her current position as the assistant director of patient-transport services.

Working in a field that is predominantly female, Martin said she’s frustrated by the lack of women in leadership and management positions. Throughout her own career progression, she’s had to fight for equity in the workplace.

Several years ago Martin interviewed a male candidate for a position directly beneath hers.

The candidate was stellar, Martin said, but he was asking for a salary higher than what she herself was earning.

One of Martin’s superiors, who was male, sat in on the interview. He pushed to give the candidate the high salary.

“I said, ‘You know what, I don’t make that much money and you never fought for me to get any advancement,’ ” Martin said. “ ‘But you’re willing to bring somebody in that works under me, and you’re willing to fight for them to get a salary that’s above mine?’ That was an eye-opening experience for me.”

Since beginning her career at Ohio State, Martin has earned undergraduate and graduate degrees from the university. Even so, she said her paycheck doesn’t always reflect her hard work.

“I’ve been told, ‘You need more education.’ So I went and got that. I was told, ‘You need more experience.’ I went and did that. So everything you’re being told to do, you go and do,” she said, “But yet you still don’t see the increase in your salary.”

In Academia

Aside from the medical center, the gender pay gap also is apparent among professors and administrators in higher education, where not only do women tend to work in lower-paying fields, but they also are less represented in senior positions.

The number of women decreases through the progression from assistant professor to associate professor to professor.

With nearly equal numbers of male and female assistant professors, the two earned about the same median wage in 2016 ($82,012 and $79,580, respectively).

However, in the same year, there were roughly 1.4 times as many male associate professors as there were female associate professors, with men earning about $6,500 more than women.

Of the university’s professors in 2016, 73 percent were men. The gender pay gap at this level was higher than the previous two positions, with men earning about $11,000 more than their female counterparts.

Despite the disproportionate representation of women across all levels of professorship, women were better represented in 2016 than they were in 2006.

In those 10 years, the proportion of female assistant professors grew by 3 percent, associate professors by 7 percent and professors by 10 percent.

The disproportionate representation of women in senior positions is not limited to professors. Women are not equally represented in many leadership positions across the university.

The Women’s Place at Ohio State works to educate female employees and provide them with opportunities for growth and leadership positions. As part of these efforts, it produces an annual progress report detailing the comprehensive status of women at Ohio State and tracking the number of women in positions of leadership, such as department chairs, deans and senior administrators.

Its data shows that in 2016 women made up 26 percent of the university’s department chairs.

However, the Women’s Place data does show improvements over time in the representation of women as vice presidents and in senior administrative positions.

McGoldrick, the university HR representative, said that’s important because as more women fill vice president positions, it’s more likely for them to be promoted to even more senior positions in the future.

“You have to look at pipeline talent and I think we’re making tremendous progress with regard to associate and assistant VPs,” she said. “And I think [Ohio State is] making tremendous progress with the director level and that’s the pipeline for future talent to the top.”

Why does the gender pay gap persist?

The existence of the gender pay gap is a multifaceted issue, with experts pointing to several causes. One is that women tend to work in fields that pay less than fields dominated by men.

This is especially relevant to academic institutions like Ohio State, where employees from a wide array of fields are represented, from the fine arts to engineering to the social sciences.

Last year, for instance, 18 of the 71 employees who worked in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering were women, while in the College of Social Work, 61 of 74 employees were women.

The median salary of employees in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering is $99,837; the median salary of employees in the College of Social Work is $72,000.

Miller said this is called “occupational segregation,” and it reflects societal views that devalue the work traditionally performed by women.

“As men enter a field that used to be predominantly female, wages increase for the field, but when women enter a field that used to be predominantly male, we see a decrease for the field,” Miller said. “So there’s a lot of evidence that men and women’s labor is valued differently even when the job requires similar amounts of education or training.”

Another reason the pay gap exists is that women are more likely than men to work fewer hours or to take time out of the workforce to raise children or care for family members.

“This has resulted in disrupting their salary history and work history, which reduces their wages when they return to the workforce,” Miller said.

And even if women do continue to work while raising children, Miller said they often work fewer hours. That can be at least partly attributed to societal expectations, which place child care and housework responsibilities primarily on women.

Those expectations are beginning to change, Miller said, but slowly.

At Ohio State, 70 percent of the university’s part-time workers are women.

While this is down from an 80-percent female majority in 2006, the number of part-time workers at the university is increasing.

In 2006, part-time workers made up about 18.5 percent of the university’s employees. A decade later, that portion of the workforce increased to 26.9 percent.

Finally, the gender pay gap can also be partially explained by discrimination and bias.

“Even when you control for all of the other factors, we still see that there’s a difference and we generally attribute that to bias and discrimination,” Miller said. “There is still lots of anecdotal evidence and some statistical evidence showing that women are still being treated less because they’re women.”

Although the pay gap is much narrower when controlling for variables such as field, rank or time employed, it still exists on a national level, according to research from AAUW.

“That’s still thousands of dollars a year for most people,” Miller said. “And even if (the gender pay gap) can be partially explained by hours or things like occupational choice, it’s still a 20 percent gap in their paycheck. That number is a real paycheck number.”

The impact of the pay gap

For Martin, those thousands of dollars could play a large factor in paying for daily living expenses.

“Do you know how much it costs to dry-clean your clothes?” she asked. “You’re expected to be a certain way, look a certain way, but where does all that money come from?”

Women gather at Goodale Park on International Women’s Day on March 8. Credit: Sheridan Hendrix | Oller Reporter

The impacts extend well beyond dry-cleaning. For many women, having a higher salary would allow them to better provide for their children.

“Women’s wages are increasingly a primary source of income for a family,” Miller said. “It has become much less common for men to be the sole breadwinners in the current era, so the fact that women’s paychecks are smaller is increasing poverty rates.”

In Columbus, one in four women are economically insecure, according to the city’s website. Females in the city earn $.78 per every $1 a male earns.

The pay gap also has an impact on women trying to pay off student loans, Miller said, with women on average taking about two years longer to pay back those loans than men.

“That’s two years when women could be saving for retirement,” Miller said.

Despite the impacts of the gender pay gap, change for women is slow to come. While Miller said the pay gap has narrowed in the past 20 years, the rate of this narrowing is slowing down.

“I think it affects us so much that it just becomes our norm and we just accept it,” Martin said. “That doesn’t make it fair, doesn’t make it right, but that’s just how it is.”

Moving Forward

To address the issue of pay inequality, Ohio State’s Office of HR is redesigning its compensation and classification system, with the hope that standardizing job descriptions across departments will allow the university to compare employees’ wages on a more level playing field.

Currently, job descriptions and titles are determined by individual colleges and departments, meaning a program coordinator in one department could be doing an entirely different job than a program coordinator in another department.

Standardizing job descriptions and centralizing compensation information is an important step toward ensuring all Ohio State employees are paid fairly, Newcomb, HR’s director of technology, process and data solutions, said.

“That gives us the quality level of data and the consistency in the data to be worth driving top-level decision-making,” he said. “It would be difficult to do a lot of decision-making on the data we have today because we’re missing so much of what we really need to do the analysis properly.”

Once this redesign is completed, Davey said it should be easier and more effective to address specific disparities in pay among university employees.

“In the past, what we’ve done regularly is, to the best of our ability, take a look at gender pay and other aspects of our compensation system at that university, but we’ve had to do that in these silos, and we’ve done that consistently for years,” he said. “What’s more recent is a universitywide effort to consolidate all of the data across the various enterprises of the university, and that’s a large undertaking at a place like Ohio State.”

The project is expected to be completed in four years, and is part of Columbus’ initiative to reduce the gender pay gap.

Ohio State pledged to support this commitment in April. As part of the initiative, introduced by the Columbus Women’s Commission, the university is not required to submit any pay or employment information to the city, but is encouraged “to share best practices and experiences with other signatories in order to improve our community’s overall gender and race-based wage gap and achieve pay equity,” according to the initiative’s web page.

In addition to this, Ohio State has created several entities to advocate for female university employees.

In addition to the work done by The Women’s Place, the President and Provost’s Council on Women provides recommendations to the university’s leadership to promote gender equity in the workplace.

Women like Martin are taking a stand to advocate for other females, too.

Martin created a luncheon series called “Women Moving Forward,” designed to encourage women to continue their education.

Through that program, Martin shared her story.

Before she reached the age of 21, Martin had five children and no high-school diploma. Since then, with the help of mentors and friends, she’s fought to overcome obstacles to reach the management position she’s in today.

“I knew there were a lot of women like me who felt that going to college was not an option,” Martin said. “They heard my story, and I’m someone that looks like them, that’s worked just like them, so they hear how you can go to school and work at the same time, and realize that it is a possibility.”

She said she hoped that by hearing from women who successfully overcame challenges, others would be inspired to further pursue their education and advance their careers.

The luncheon series was successful, with several women registering for classes at Ohio State or Columbus State after participating. Others pursued resources to obtain their GED or sought career advice.

Even so, she said she’s not expecting equality in women’s pay at Ohio State in the near future.

“Do I think there’s going to be a change soon?” Martin said. “You know, I don’t know. I don’t know. Because if the facts don’t promote change, I don’t know what will.”