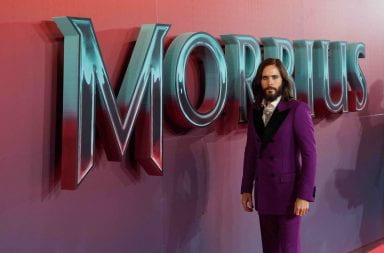

A poster for the movie ‘The Interview’ is seen at the AMC Glendora 12 movie theater. The three largest theater chains in the U.S. — Regal, AMC and Cinemark — have decided not to screen the movie when it debuts Christmas Day.

Credit: Courtesy of TNS

Christmas Day has long been a lucrative holiday for movie theaters.

Yet box office revenues were at risk of looking quite different this year when an anonymous group got online and threatened violence in response to the Dec. 25 release of “The Interview.”

The low-brow comedy stars Seth Rogen and James Franco as man-children prompted by the CIA to assassinate North Korean Supreme Leader Kim Jong-un.

Kim’s personality cult is easy fodder for a comedy — but it was also apparently blasphemous, and Pyongyang was not happy.

In June, North Korea called the movie an act of war and promised “a merciless counter-measure” if it hit theaters. The movie’s parent company, Sony Pictures, saw its first consequences Nov. 24, when cyberattacks by a group calling itself the “Guardians of Peace” exposed emails and employee records (including social security numbers) from the company.

North Korea denied involvement, even though the malware used in the attack was written in Korean and was identical to the same used in a 2013 attack on South Korea. FBI investigators announced Dec. 17 that its evidence indicates the attackers were working under direct orders from the North Korean administration.

On Dec. 16, the “Guardians of Peace” warned movie-goers to stay home upon the release of “The Interview,” threatening 9/11-style attacks.

Despite Homeland Security denying any credible evidence of attack, the threat prompted many theater chains — including AMC, Cinemark and Regal Cinemas — to pull the film from their schedule. Sony Pictures soon followed by canceling a theatrical release altogether.

In a Wednesday statement, Sony Pictures claimed to “completely share (theaters’) paramount interest in the safety of employees and theater-goers.

“We stand by our filmmakers and their right to free expression,” the company ironically added while doing the very opposite.

The sad truth is the only “safety” threatened in this situation is that of box office earnings. Pyongyang is notorious for its war games to intimidate its enemies, and the West has appropriately ignored the empty threats.

Mitchell Lerner, the director of OSU’s Institute for Korean Studies, said that while North Korea might likely be responsible for cyber attacks, any actual violence by the nation is highly unlikely.

“They launched similar cyber attacks in recent years against South Korean banks and media studios,” he in a Thursday email. “But they don’t have the ability to launch a physical attack against the United States of any real significance. Nor is there any reason to think that they would. (North Korea) is indeed a very rational actor, and they know that any attack against the U.S. would lead to a retaliation that would be devastating.”

While Hollywood thrives on controversy and publicity, Sony’s decision was probably a simple reaction to major theater chains pulling out, he speculated.

Hollywood, however, also knows that the American public is more likely to overestimate the danger of North Korea, and the threats of violence are likely to keep many Americans from going to the theaters after Christmas.

By canceling “The Interview”’s release, Hollywood can at least ensure that the other movies on the marquee get an audience, including the Sony-backed “Annie.”

Unfortunately, this sort of intimidation is nothing new. In 1988, more than 3,500 American theaters refused to screen Martin Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ,” and a fundamentalist group injured 13 people in a Molotov cocktail attack on a Parisian theater screening the movie.

Despite the backlash, Universal Pictures still had the gall to put out the movie in Christianity-dominated countries.

What if they hadn’t? What films could have been derailed in that wake? Perhaps an extreme anti-gay group could have kept “Philadelphia” off the screens with enough threats. Could the Feds have persuaded theaters “JFK” was potentially riot-inducing and limited its run?

These scenarios aren’t any more far-fetched than when the tantrum of an isolated, powerless East Asian nation ended the distribution of a $44 million movie.

Whether Sony Pictures knows it or not, it has set a dangerous precedent for self-censorship in movies.

In the U.S., it’s long been held that the American consumer votes with his dollar. Unfortunately, the consumer won’t be given that chance this Christmas.

Instead, Sony Pictures has tacitly sent the message that if a single actor is loud enough or intimidating enough in its opposition, it can be successful in getting its way.

This concession on the studio’s part will only encourage future radicals to make the same sort of threats North Korea has, now with the assurance that they can prevail.

Unless Sony Pictures reverses its course of action, this could become a standard practice, and the next time movies like “The Last Temptation of Christ” arouse the fury of a radical minority, they’ll be less likely to even hit the screen.