During my freshman year at a Midwestern university, an anthropology professor in her first lecture declared black people have the remnants of monkey-like tails. The professor matter-of-factly told the class she would have ordered me to drop my pants to display my anthropoid anatomy but she felt such a “show-and-tail” might make some of the white female students uncomfortable. This professor’s expression of unrestrained racism impelled me to excel in her course. I earned the top scores on both the midterm and the final, but the professor failed me in the course. She accused me of cheating on the final despite acknowledging she had absolutely no proof I had. Her only evidence was her belief that blacks were intellectually incapable of scoring 100 percent on her test. I appealed to the head of the anthropology department, a Kenyan. He said although he sympathized with me, he couldn’t do anything since it would seem that he was siding with me because we both were black. The failing grade stood. A lawsuit filed recently seeking to dismantle affirmative-action programs at the University of Michigan reminded me of the bigotry I confronted in college 28 years ago. The group that initiated the Michigan lawsuit, Center for Individual Rights, succeeded in getting a federal appeals court to eliminate affirmative-action admissions last year at the University of Texas Law School. Numerous witnesses in the trial preceding that 1996 appeals-court ruling testified about a hostile racial environment at the University of Texas Law School. They cited professors who make racist slurs and proclaim their low expectations of minority students. Ironically, a pivotal 1950 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, Sweat vs. Painter, outlawing the racist exclusion of qualified blacks at the University of Texas Law School laid the foundation for the seminal 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision ending legalized segregation in America.Two things have always amazed me about the assaults on affirmative action in academia: These assaults never attack traditional preferential admissions such as for the children of alumni, and these assaults ignore the history of racism.In 1994, a federal appeals court voided a minority-scholarship program at the University of Maryland, a school segregated by law until 1954 and by policy until 1970. The appeals court stated the historic segregation at the University of Maryland could not “justify a race-exclusive remedy.” But why not? That university has a long way to go toward equality precisely because of its history. Far from promoting colorblind admissions, the incessant assault on affirmative action in the academy serves to perpetuate the exclusionary practices that made affirmative-action programs necessary in the first place. I didn’t fail that anthropology course because I was genetically inferior or because I fooled around instead of studying. I got an F because a professor couldn’t hide her racism. Many of today’s affirmative-action opponents cloak their racism behind the rhetoric of blacks being unable to compete academically. Now they are giving us F’s even before we enroll.

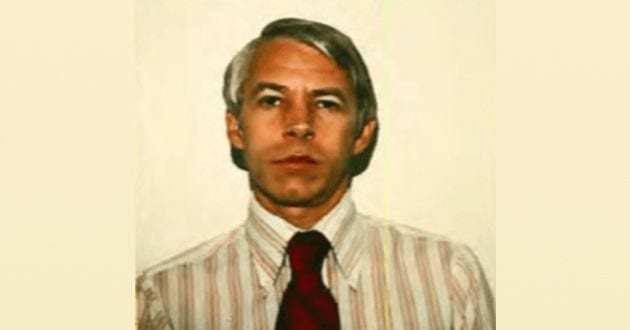

Linn Washington Jr. is a journalism professor at Temple University who writes frequently on race issues.