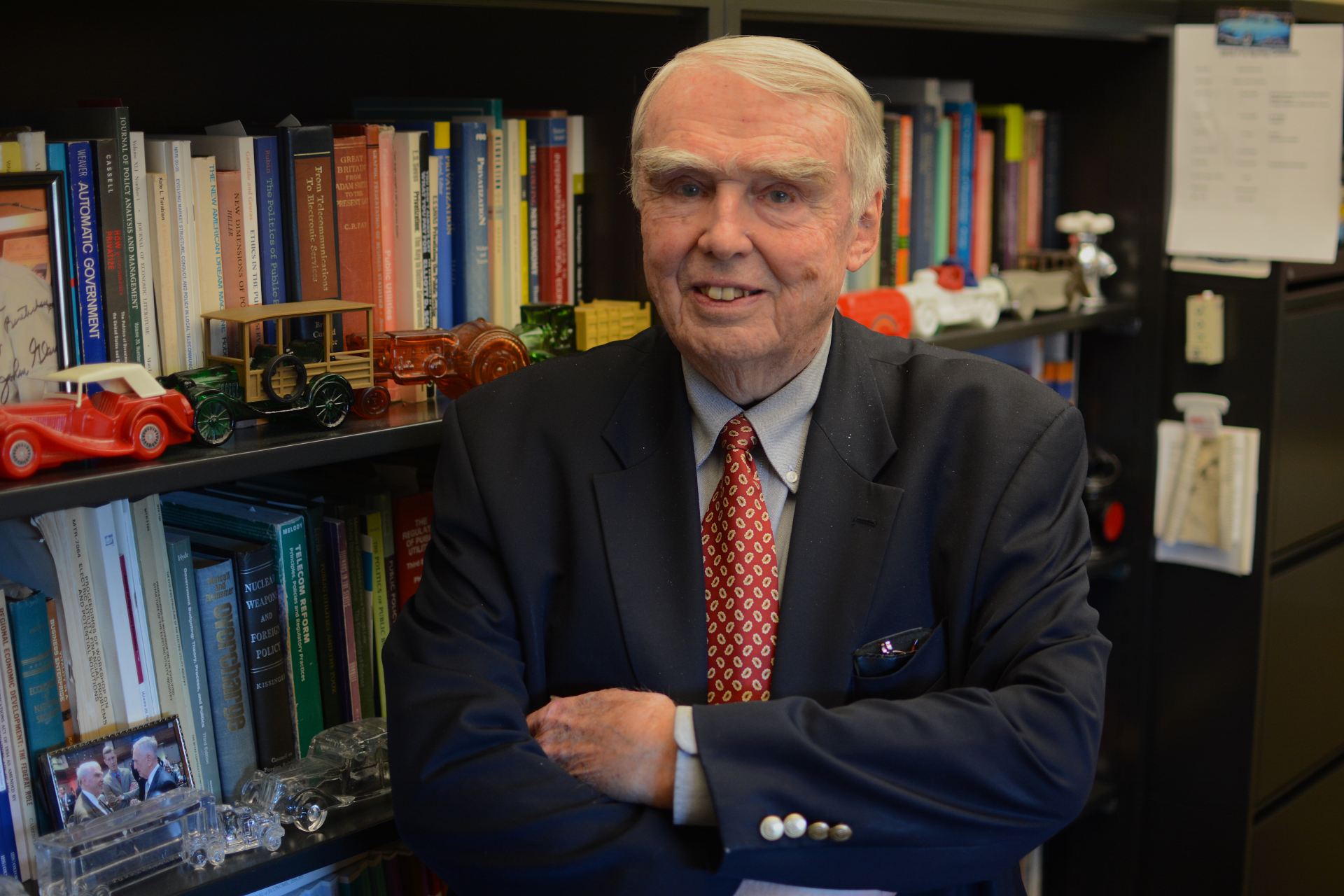

Doug Jones, a professor emeritus of public policy and management in the John Glenn College of Public Affairs, in his office at Page Hall. Jones helped former U.S. Sen. Mike Gravel submit the Pentagon Papers into the public record in 1971. Credit: Kevin Stankiewicz | Editor-in-Chief

Doug Jones received the phone call from former Sen. Mike Gravel a little after 10 p.m. He was asked to come to the senator’s house — with a toothbrush. When he arrived, expecting a long night, Gravel met him at the door. He said he had the Pentagon Papers and planned to release them to the public the next day.

Gravel asked Jones if he was aboard.

Jones, now a professor emeritus of public policy and management at Ohio State, didn’t hesitate to say yes.

At that time — the summer of 1971 — the majority of the public was against the Vietnam war, Jones said recently while reflecting on that year in an interview with The Lantern. Then Gravel’s legislative assistant, Jones also “had crossed over on the war a long time before that night.”

On that night — June 28, 1971 — the top-secret and classified Pentagon Papers sat underneath Gravel’s bed. They contained more than 1,000 pages of a 1945 to 1967 historical study on the Vietnam War that would eventually expose the lies told by presidents and politicians to the world.

“The papers reveal so many lies and misleading information about the regime,” Jones said. “The content showed so much deception.”

The New York Times and Washington Post obtained the study and published articles on the information that week, including some snippets of the papers. The newspapers were sued by the federal government and a temporary restriction prevented them from reporting more on the documents.

There are times when the stakes are high enough, and the deceit is gross enough, that the proper grounds is to disclose it. The game on deception was up. – Doug Jones, professor emeritus of public policy and management.

Jones took part in a story not told by the critically acclaimed new movie “The Post,” which focuses on The New York Times’ and Washington Post’s efforts in publishing the Pentagon Papers. Jones helped Gravel release the papers in a different manner — reading them at a Senate subcommittee meeting, thus placing the words in public record.

With three other legislative assistants, Jones spent the night combing through the papers and redacting names that could not be released to the public. At about 3 a.m., Gravel went to sleep, but not before letting his aides know the plan: He would call for a quorum on the Senate floor and read the papers then.

Jones’ stop at Gravel’s home came after the New York Times and Washington Post publications, but each was in the midst of a lawsuit handed down by the Department of Justice.

The lawsuit sought to prevent the news organizations from releasing the information to the public — but if Gravel did so himself, the lawsuit would essentially be null, Jones said.

The Democratic senator from Alaska and his staff were “flying in the face of a court decision,” Jones said.

After a night of weighing the pros of reading the papers before the Senate — the information could shorten the war and save lives — and the cons — potential jail time for all involved — Gravel, Jones and three other staff members had successfully combed through the thousands of pages.

“You knew that you were on the edge of high drama,” Jones said. After a sleepless night, he awaited the anticipated quorum, but said the Republican senators knew something was astray; they blocked anything from happening by refusing to enter the Senate chambers.

What Jones didn’t know was Gravel had a backup plan: he called a subcommittee meeting that he was in charge of at 10 p.m., 24 hours after he called Jones and his aides over to his home.

Only one congressman was in attendance, but that was enough for the meeting to be official.

“[Gravel] started to read the Pentagon Papers, he read for a couple of hours and then he broke down crying,” Jones said. “Partly because of the stress.”

Ohio State Professor Emeritus Doug Jones holds up one volume from the collection of documents known as the Pentagon Papers. Credit: Kevin Stankiewicz | Editor-in-Chief

Because Gravel was the only senator in the session, his one vote was the only that mattered. He voted in-favor to submit the meeting minutes — the papers, the lies, the deception — into public record.

“It was a very important moment,” Jones said. “The Republicans were furious.”

After that day, Gravel was sued by the Department of Justice, but he faced no punishment because he was found to be working in “the legit pursuit of Senate business,” Jones said. “After all, war and peace is Senate business.”

The ruling said the staff has Senate immunity, as well. On June 25, 1971, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of The New York Times and Washington Post, allowing them to continue publishing the material.

If the reading would have happened a day or two after, Jones said, the ruling on the newspapers “could have gone the other way.”

“I’ve never plotted through the other 3,900 pages,” Jones said, though he owns hard copies of different volumes published.

Jones said he is and was “no whistleblower,” but the act he helped put forth created a new means of getting information out to the public.

“There are times when the stakes are high enough, and the deceit is gross enough, that the proper grounds is to disclose it,” he said. “The game on deception was up.”