Ohio State isn’t sitting around waiting to see what laws the U.S. government passes. Instead, it’s doing its best to influence those decisions.

Over the past few years, OSU has spent more than $200,000 annually seeking influence on issues from agriculture to veterans affairs in Washington, D.C. One expert said that’s not an unusual amount.

OSU, as well as other universities, is working to make itself heard through lobbyists who advocate to convince senators and representatives to take its side on pieces of legislation. To do this, OSU must spend money.

“We’re affected by the federal government, and they play a very big role in supporting education and research at Ohio State,” said Stacy Rastauskas, OSU associate vice president for federal relations.

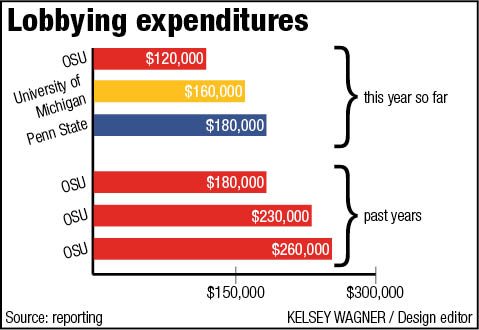

The university has reported spending $120,000 on lobbying efforts for the year through June 30, including $40,000 for the second quarter of the year.

That figure for the second quarter, however, was noted as $150,000 on July 21. It was later changed because of a calculation error, Rastauskas said.

“We incorrectly reported the total dues paid to several national associations in that quarter, versus the percentage of dues spent on lobbying,” she said.

Lobbying costs includes a variety of factors, Rastauskas said. One part of the cost is the percentage of work time an employee spends making lobbying contacts multiplied by that person’s salary. That could include people in the Office of Government Affairs like Rastauskas, OSU President Michael Drake, the senior vice presidents, deans and directors.

It also takes into account a certain percentage of dues the university pays to national organizations for higher education, medical centers and others that advocate on the university’s behalf.

“If you look at our $5.5 billion university budget, you could probably say that more than half of the revenue that comes into the university is directly or indirectly coming from federal and state government,” said Herb Asher, senior vice president for government affairs.

“If so much of your revenue is coming in from government, you want to be able to influence them,” he said.

In 2013, the university spent $260,000 on lobbying efforts, with $190,000 coming from the first half of the year.

Although the lobbying costs have stayed relatively consistent in recent years, the salaries of some OSU officials involved with that lobbying have risen.

For example, Rastauskas’ salary rose nearly 57 percent to $228,024 in 2014 from $145,260 in 2012. And Asher’s salary rose about 5 percent to $236,385 in 2014 from $225,000 in 2012.

The Office of Government Affairs gives senior university leaders information about trends in Washington, D.C., and what’s going on in different areas of campus so they can make informed decisions in the lobbying arena, Asher said.

“The president, the provost, the trustees, and others, are really helping to identify what the university priorities are, then the government affairs team is trying to advance those priorities,” he said.

The total budget for the Office of Government Affairs for fiscal year 2014 is nearly $2 million, OSU spokesman Chris Davey said. That number accounts for the Columbus and Washington, D.C.-based offices and includes salaries, benefits, rent, office supplies and services for both.

As one of the largest universities in the country, OSU is in the upper tier of collegiate spending on lobbying, but that’s not surprising, said Dave Levinthal, senior political reporter for the Center for Public Integrity.

“It serves to reason that you’re going to have a strong lobbying presence in Washington, D.C., relative to all schools across the country,” Levinthal said.

Other schools are spending big bucks as well, with the University of Michigan doling out $160,000 and Penn State spending $180,000 in the first half of this year.

Universities and other higher education institutions often band together to push certain issues — like basic educational issues, budget issues and transportation issues — that affect all colleges, Levinthal said.

“So many of those decisions that get made in Washington have a direct bearing on the communities that the universities operate in or the universities themselves,” he said.

Rastauskas said Washington, D.C., is a neutral zone from rivalries like that between OSU and Michigan.

“As they say, the rising tide lifts all boats,” Rastauskas said. “We’re in it together. Not on the football field, but on the lobbying field.”