Monica Cox has known about the difficulties of being a minority since she was a child.

The only daughter of two parents who lived in the Jim Crow South, she grew up just 7 miles from where her ancestors once worked the Alabama land as slaves. As she became older, her parents shared with her what it was like to see Martin Luther King Jr. and the Montgomery Bus Boycott firsthand.

One principle they continually instilled in Cox was that she had the potential to be anything she wanted — a lesson she has carried into her professional life.

Flash-forward a few decades, and Cox sits at the head of Ohio State University’s Department of Engineering Education. It is a position in a white, male-dominated field that is rarely filled by a woman — let alone a woman of color.

“It was important for me to work with my male students, my white, male students — people who had never engaged with a female professor or a professor of color,” said Cox, who was named chair in 2015.

Cox wasn’t just imagining things. She is right. According to Ohio State official faculty statistics, the percentage within the engineering department was minuscule: .005 percent. And black women were totally absent in 2014, the most recent year faculty demographic information was made available to The Lantern during the investigation.

Monica Cox, the Department Chair of OSU’s college of Engineering describes what it is like to be a black woman who works in a dominantly white male field. Credit: Jenna Leinasars | Former Assistant News Director

The lack of diversity among Ohio State professors is not limited to her field. It is present in many academic disciplines, and begs the question, “Who should the faculty and students represent?”

Ohio State is positioned at the center of Columbus, Ohio, a municipality that boasts higher-than-average diversity percentages than the state as a whole. In many racial categories, the difference is nearly double. For instance, in the 2010 census, the most recent non-projected report, Columbus has a black population of 28 percent. Ohio’s black population statewide was 12 percent.

The university also has a substantial number of undergraduates, which has grown each year since 2011. In 2014, the undergraduate population on Columbus campus was 44,741 students.

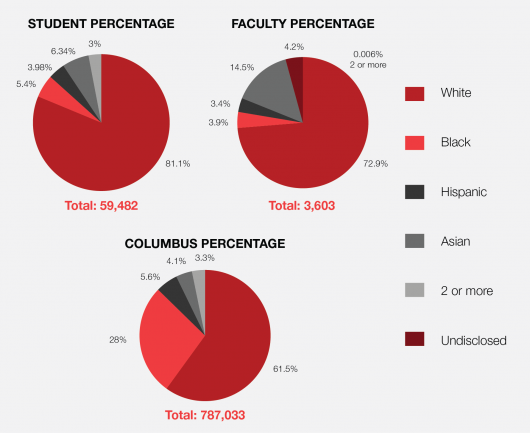

Compared with the student body and Columbus population, university faculty underrepresented the demographic makeup of white, black, Hispanic, and those with two or more ethnicities.

This wasn’t the case for the Asian population, which made up 14.5 percent of total faculty in 2014 whereas the Asian undergraduate population was 6.34 percent and the Asian population in Columbus was 4.1 percent.

University administration acknowledges Ohio State has not met its ultimate diversity goals.

“We’re not the very best,” said university spokesman Chris Davey. “We’re certainly not where we want to be, but increasingly we’ve done better and better against our goals and our peer institutions.”

Within the entire engineering department in 2014 there was only one reported black professor, one documented professor registered with two or more ethnicities and nine Hispanic professors. The department was home to 215 professors.

At that time, 60 percent of professors were white and 24 percent were Asian.

Cox said she feels underrepresented in the engineering department in more ways than just race.

“You are different. You are an outlier and it’s real,” Cox said. “I do feel that because this is the nature of the profession. It’s very male. It’s very white.”

At times, the white-dominant workplace affects her relationships with other staff members, Cox said.

“You have to overcome your implicit biases or even sometimes explicit biases to work with someone who is different,” she said. “There’s a personal transformation or personal reflection or experience that someone goes through trying to reconcile what they knew and what they think.”

The data also showed Ohio State’s largest college has an overwhelmingly white faculty. Out of the 867 College of Arts and Sciences professors who chose to identify their race in the faculty survey, four out of five in 2014 were white.

In comparison, one out of 25 professors in the College of Arts and Sciences was Hispanic.

Three out of four professors in the College of Medicine were white, with the next greatest proportion being Asian — four out of 25 professors were Asian.

You can also count on one hand the number of Native American professors across all colleges.

The diversity statistics on campus came as no surprise to Gisell Jeter-Bennett, an intercultural specialist for Women Student Initiatives, an office within the Student Life Multicultural Center.

Giselle Jeter-Bennett discusses her opinion on institutional racism and higher education. Credit: Jenna Leinasars | Former Assistant News Director

“This is my ninth year at Ohio State and in that time I’ve earned a master’s and a Ph.D. so the numbers don’t surprise me, but I think it’s also typical of predominantly white institutions,” Jeter-Bennett said.

“I think it just goes back to how our nation functions from a racial perspective,” she said.

She added diversity is not just an Ohio State issue, it’s a higher-education issue — as well as an issue throughout America.

“There is some systemic racism in America, and it is still alive and well,” Jeter-Bennett said.

Student comparisons

At Ohio State, the student demographic makeup is closely aligned with that of professors. However, not all students feel fairly represented.

Sydney Miller, a fifth-year in history of art, is the president of the Native American and Indigenous Peoples Cohort. She identifies as half-black and half-Native American and is part of the Southern Ute Mouache Band in Ignacio, Colorado.

She was not surprised that there are only five Native American professors on the Columbus campus — because she has known all of them for years.

“They’re basically all of my elders growing up here on campus,” she said.

Miller said elders provide emotional, academic and religious guidance for those who are away from their tribes.

“(Some schools) have an elder on campus. They pay them to be that elder, so they’re that resource for us to have a spiritual connection, and we don’t have that here,” she said. “We don’t have a way to connect with that spiritual element of (being Native).”

Miller said it would actually be more unusual for her to encounter a professor who was Native American as opposed to one who was not. She said she’s gotten used to being alone in her identity.

In 2014, professors who identified as Native American only had a presence in three Ohio State colleges — Arts and Sciences, Food, Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and Medicine.

Without her participation in NAPIC, Miller said it would have been difficult for her to identify with her native heritage and continue to attend Ohio State.

Cox said for many students, seeing themselves in their professors is crucial, but seeing a professor who might not look like them, or have the same sexual orientation, could also be incredibly beneficial.

She said she thinks it’s important for students of all races to see diversity in professors because it allows for students to see themselves in roles they could have in the future.

“That’s a pathway that somebody else has paved that’s important to you,” Cox said.

Seeing somebody who is of a different race, gender or sexual orientation as a professor, she said, could push students academically.

“It pushes students to think in a way that’s very different than how he or she was brought up,” Cox said. “I think it’s really easy to be in a comfort zone, but if you go out into a workplace or if you work in a global environment, you’re going to have to be very sensitive to people of different cultures and understand how to communicate with people to get your work done.”

The university also acknowledged some demographics have not seen an enrollment increase over the past few years, with the main group being African-American male students.

“If you talk about diversity in general, Ohio State has had success in recent years in improving the overall diversity on our campus, but we have fallen short in some areas, and one of those is in African-American men,” Davey said.

During a 2017 radio interview, University President Michael Drake said Ohio State is actively involved in outreach in many areas.

“We have provided programs — our Young Scholars Program, for one — we’ve increased really significantly over the last two years,” he said. “Among others, I travel during the year and during the summer to places where we have talented students who haven’t been applying in the numbers we would like to see to encourage them to apply.”

Drake is involved in the American Talent Initiative, a meeting of university presidents to share outreach ideas on increasing the students of nontraditional, low-income, minority backgrounds who apply to higher-education institutions. He’s also on the steering committee for the initiative.

“We want to try to open that pathway of access and then do our best to support those students. It’s something we think about on a daily basis. It’s really, really important to us,” Drake said. “Last year (Ohio State) had the greatest number of applicants in history, but we also had an 11 percent increase in the number of minority students on campus, which is the largest increase in our history.”

Columbus population

In the 2010 census, nearly three out of five Columbus residents were white. But the amount of white Ohio State students and faculty reflect percentages nearly 10 percent higher.

Ohio State’s black student population is underrepresented as compared with the black population of the city by a ratio of nearly 6-to-1; for faculty the ratio is 7-to-1.

The Asian student population is proportional to that of the city, hovering between 4 and 5 percent. Meanwhile, the Asian faculty percentage is almost triple, representing a sizable discrepancy.

Hispanics also held a greater proportion of the population in Columbus than Ohio State students and faculty, but by a smaller margin; in Columbus Hispanics made up 5.6 percent of the population, in the student population Hispanics made up 3.98 percent and in faculty Hispanics made up 3.4 percent.

Jeter-Bennett said as minorities take on a larger portion of society, their presence should be represented in community institutions such as higher education.

“I think more of the focus should be on how do we change the data so that it is more reflective of the community that we live in and also the nation that we live in,” she said. “So if we know that people of color — that the population of people of color is increasing — that should be reflected in our schools,” she said.

Hiring and recruiting faculty and students

With these differences across student, professor and Columbus demographic groups, what part does diversity play when Ohio State is looking to hire new faculty? Does it draw from student percentages or should it represent the greater Columbus community? The answer is not always simple.

“We have a holistic approach,” Davey said. “We take into consideration all of the applicant’s qualifications and arrive at a decision about whether they’re the right match for that particular job… Diversity is one of those considerations.”

He said Ohio State works to apply diversity to its hiring practices well before an interview takes place.

“It starts with networking,” Davey said. “The most successful approach in diversity-hiring starts at the beginning.”

He said there are various multicultural professional groups Ohio State reaches out to in efforts to network job openings and opportunities. The recruitment process is similar for student applicants.

There is no set number university admissions look at when recruiting students of diverse backgrounds, in large part because it is against the law to recruit students to meet numbers based on race, and in part because the university looks for students who are diverse in more ways than one, said Keith Gehres, director of outreach and recruitment in admissions.

“Our office is really charged by the university to build a class to meet the university goals as outlined by leadership,” Gehres said.

Hitchcock Hall, home of the College of Engineering, had no black women professors in 2014. The overwhelming majority of faculty were white, followed by Asian. Credit: Jenna Leinasars | Former Assistant News Director

These goals include diversity in academics, race, geography and accepting first-generation students.

Gehres said though the university’s goal of diversity has been prominent in the past few years, however he said there was never a specific time when admissions decided to focus on obtaining classes with more diverse and better representative backgrounds.

“It has absolutely been gradual,” Gehres said. “When President Gee was here, he used to say that it’s hard to turn a aircraft carrier around, but once you get the momentum going, you can’t stop it. That’s kind of how this process has evolved.”

Though change has been gradual, Gehres said if you look at it from an angle evaluating the past 20 to 25 years, it’s evident. And, once the carrier began its turn, Ohio State’s admission statistics have continually improved in terms of race.

Gehres has been in admissions for more than 13 years, and he said throughout his time he has never seen a year without improving admissions data — in terms of grades, GPA or diversity — since he was hired.

“We’ve been able to say every year since I’ve been at Ohio State that we are enrolling the most academically talented and diverse class in the history of the university,” Gehres said. “That’s not something you can sustain indefinitely.”

Though these achievements are notable, Gehres said there is no way to continue improving each year in all areas with class sizes and standards growing and getting higher.

He said for some students, recruitment can be a bit different. The process could include phone calls, emails and even meetings with Ohio State professors in order to ensure they feel comfortable and ready for college.

Making Strides

Though statistically, minority student populations haven’t increased drastically at Ohio State since 2014, the idea of a better representative class is on the minds of those in administration.

One major aspect of Drake’s 2020 vision — goals in which university administration works to achieve by that year — is diversity and inclusion.

As part of this goal, Ohio State is developing university-wide diversity training for search committees to hire on and recruit professors and faculty of minority backgrounds.

Additionally, Ohio State’s Young Scholars Program, which originated in 1987, is devoted to helping low-income, first-generation students from nine cities in Ohio, including Columbus.

Students in YSP — 75 percent of which are black — take college-prep courses throughout high school and work with students on study skills and other college preparation needed to be successful at Ohio State.

While in college, YSP students receive need-based scholarship throughout the four years of enrollment, have an upperclassmen mentor and meet monthly with a success coach.

This could be a reason why Ohio State is leading the nation in black graduation rates, according to a 2013 report by The Education Trust.

Ohio State spokesman Ben Johnson has hinted that this year’s incoming freshmen class is the most diverse yet, though demographic information is not yet available.

“This will likely be our most talented and diverse freshman class,” Johnson said.

Cox said the underrepresented black community at Ohio State is troubling to her, but institutional diversity is far from a simple issue.

“Higher ed … you have to look at it as an institution. It is a privilege. It’s not something that everybody does. It’s not an option that everybody has,” Cox said. “It costs money to engage in this, so the numbers don’t surprise me. It just represents some of the real issues in our society when it comes to socioeconomic differences and disadvantages to minority populations.”

Methodology

The Lantern was given student and faculty data from 2014 by Ohio State administrative officials in the spring of 2017. The faculty data included names, salaries, working titles and affiliated departments. The data was then dissected to only include main campus employees whose titles included professor, associate professor, clinical professor and assistant professor. The races included in the summaries and figures were those listed in the data set provided: those identifying as white, black, Hispanic, Asian, Hawaiian, American Indian and two or more races. Those who chose not to disclose their race were excluded from the data analysis as to not skew results.

The Lantern also pulled Ohio State main campus student enrollment data — which included both graduate and undergraduates — from the autumn 2014 student enrollment report. The student demographics data from 2014 was used as to stay consistent with the most recent faculty data that was provided to The Lantern.

This demographic data was used in comparison to 2010 Columbus census data — the most recent date the survey was conducted. Though information for the vintage year of 2016 was available, The Lantern decided to work with actual data — not projected — for this project.

Correction, 9/6 9:10 p.m.: There are four black professors in the Moritz College of Law, one black professor in the College of Nursing and one black professor in the College of Optometry. Due a reporter’s error, information about the colleges were incorrect in a story, The Lantern regrets the error.