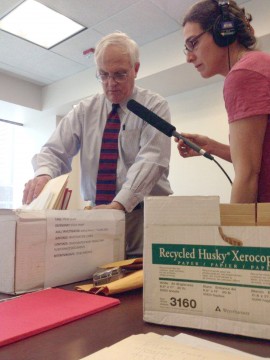

Sarah Koenig, the host of “Serial,” interviews a records custodian with the Baltimore City State’s Attorney’s Office.

Credit: Courtesy of TNS.

To no one’s surprise, Sarah Koenig’s “Serial” has become the most-listened to podcast ever.

Koenig, a longtime producer for radio show “This American Life,” co-produced and hosted the spinoff that told the story of a Baltimore teen’s 1999 murder in week by week episodes. In turn, she made every listener feel like a detective. The podcast aired a new episode nearly every week from October through December, and I finally succumbed and listened to every episode in early January. I was initially uneasy about all the hype, but after listening to only the promo for episode one, I was a fish on Koenig’s murder mystery hook.

At the beginning of “Serial,” Koenig says, “For the last year, I’ve spent every working day trying to figure out where a high-school kid was for an hour after school one day in 1999.” Koenig, who admits she is not a detective or private investigator, spent that year gathering and poking holes in the alibis of Adnan Syed, who was charged and convicted for the murder of his ex-girlfriend, Hae Min Lee, at the age of 17. Lee disappeared in January 1999 and was found strangled and buried in a shallow grave in February of the same year. No matching DNA or fibers were found at the scene, but the jury still convicted Syed because of cell phone records and the testimony of a man named Jay, who claimed to have helped Syed bury Lee’s body.

Koenig dove into this story when a friend of Syed, Rabia Chaudry, came to her with the story, insisting on Syed’s innocence. Koenig began talking to everyone involved, including Syed himself, who has been in prison since 1999 and still claims innocence, but says he remembers nothing about where he was the day Lee disappeared.

Koening’s voice isn’t particularly soothing, but she adds a personal element that allows listeners to feel like they are making this investigative journey with her. She often inserts her opinions, feelings and doubts about statements made by witnesses, but also seems to remain objective. Each episode ends on a high point, leaving the listener with a paradoxical sense of confused clarity, and a yearning to listen to the next episode to find out just who saw Syed at the time of Lee’s death, and just why Jay might be lying about everything.

This long-term reporting of such a compelling story might not be “relatable” to the general public, per se, but who doesn’t love a good murder mystery that you can listen to in the car or at the gym? “Serial” seems to have united much of the public with a common goal to find the truth.

This goal, though, could lead to something far more impactful than finding the truth about Syed’s case. When I was in between “Serial” episodes, for the first time in probably three years, my instinct wasn’t to sit down at home and turn on the television or to use my free time to browse social media. Every free minute I was thinking about Syed, Jay and Lee, trying to piece evidence together in my head until I could listen again.

This says something about the radio/podcast medium. If Koenig continues with the series, and other journalists decide to take on similar tasks on such a large scale, I wouldn’t be surprised to see a decline in Netflix subscriptions. With more than 5 million downloads within a month and a half, iTunes recently reported “Serial” is the first-ever podcast to reach that number of downloads so fast. If people start listening to podcasts like “Serial” while on the go, it’s possible that the interest will remain when they get home. Who knows, maybe the norm for the second half of this decade will be for families to gather around a podcast after dinner and follow up with some in-depth discussion instead of mindlessly staring at screens until bedtime. Perhaps even millennials will start to use Twitter as more than a place to vent about how annoying their professors are.

Since “Serial”, petitions and hashtags like #FreeAdnan are swirling around the Internet, getting people involved in a case they otherwise would have probably never cared to hear. Chaudry is very active on Twitter, and posts to the #FreeAdnan hashtag regularly. Jay also recently agreed to an interview with news website “The Intercept,” in which Chaudry claims proved he committed perjury during Syed’s trial. Chaudry has also started a Twitter campaign for a legal defense fund for Syed, hoping to raise $250,000 to “cover the cost of a possible appeal.”

I personally think Adnan is innocent on the grounds that there just wasn’t enough evidence to prove him (or anyone else) guilty. Whatever happens with Syed’s case, I will have my headphones ready and waiting to hear that familiar theme music if Koenig decides to report on Syed’s case further before moving onto another mystery.