He couldn’t talk. He couldn’t move. He couldn’t cry.

Jacob Bruner, an OSU graduate, could only bury his head under his pillow and ask himself, “Why did this happen?”

His mother had just told him that his hero, his older brother, had committed suicide.

“There are questions that go unanswered to this day,” said Bruner, who graduated with a degree in political science in 2013. “And that’s why I think suicide is so rough: You don’t really have any closure on why someone did it.”

Many families like Bruner’s ask the same questions about suicide.

Young adults age 20 to 24 are the highest risk group for suicide among youths, said Cynthia Fontanella, clinical assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral health at the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center and lead author of a new study focusing on youth suicide rates.

The study, published in March in JAMA Pediatrics, found that the youth suicide rate in rural areas was nearly double that of urban areas from 1996 to 2010, and that the rural-urban suicide rate disparity could be widening.

Researchers offered several possible explanations for high rural suicide rates, including access to firearms, geographical and social isolation and access barriers to mental health services in rural areas.

Fontanella said the researchers identified three possible approaches to improving access to services in rural areas: integration of mental health care within physical health care, improvements in telemedicine, and school-based intervention and prevention training.

“There’s an urgent need to improve access availability and acceptability of services in rural areas,” she said.

Researchers analyzed national mortality data from 1996 to 2010 from the National Center for Health Statistics National Vital Statistics System, identifying about 67,000 suicides between 10- to 24-year-old youths.

The study also found that hanging has become the predominant method of suicide among young adults of both sexes, showing a decrease in firearm use.

Suicide rates are four times higher among young men than among young women, Fontanella said.

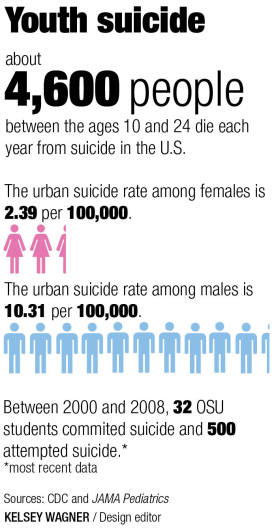

Rural suicide rates among males were 19.93 per 100,000, compared to 10.31 per 100,000 in urban areas. Among females, rural suicide rates were 4.40 per 100,000, compared to 2.39 per 100,000 in urban areas.

Dr. John Campo, senior author of the research and chair of psychiatry and behavioral health at Wexner Medical Center, said suicide risk factors among youths can include mood disorders, genes, aggression, depression and depressive disorders associated with puberty development.

He said suicide and violence are among the top three causes of death among young adults, with many incidents involving substance abuse or mental health, both prevalent factors in suicides.

“Our priorities are out of kilter with the realities of the public health problem,” Campo said. “One of the issues that drives this is that we don’t take this problem seriously enough, largely by virtue of how we think about it.”

He said one barrier to improved care might be rooted in the framing of the issues of suicide and mental health.

“We tend to think about these problems as things that people do to themselves, so instead of an illness or disease that you’re victimized by, we tend to think about this as more of a socio-moral problem than a public health problem,” he said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that about 4,600 people between the ages 10 and 24 die from suicide each year.

Between 2000 and 2008, 32 OSU students committed suicide, with 500 students attempting and 4,000 seriously considering suicide each year at OSU, according to a 2008 OSU College of Education and Human Ecology newsletter.

Fontanella said she thinks there is room to improve access to services and identifying high-risk students at OSU.

“We need to do more at Ohio State,” she said. “We could do better on campus about getting counseling, reaching out, educational awareness and campaigns around suicide.”

As a freshman, one year after his brother’s suicide, Bruner came to the same conclusion.

In October 2009, he founded the Buckeye Campaign Against Suicide, a student-led organization focusing on suicide prevention through awareness and activism on campus.

“It’s all about reducing the stigma, increasing visibility, getting students involved and showing you can be part of the organization, even if you haven’t had a personal experience with it but just want to make a difference on campus,” Bruner said. “And I think we did that.”

Lex Clark, president of BCAS and a fourth-year in industrial and systems engineering, is helping to continue that mission. She worked as coordinator of the third annual R.U.O.K.? Day on March 3 at the Ohio Union.

The event aimed to raise awareness among students and promote available university resources.

“This is really big in our society, and the importance of having events like this is that it’s going to make a huge difference in more than one person’s life,” Clark said.

BCAS is currently working in collaboration with OSU’s Gamma chapter of the Sigma Pi fraternity to plan the Best Day of Your Life event for early April, Clark said. The event will include prizes and activities, providing an opportunity for participants to learn about suicide prevention.

Fontanella said reaching out is a positive way to combat a sense of hopelessness, a key factor for a suicidal person.

“We need to reach out and let people know that we care, and take it seriously,” she said. “It’s one person at a time.”

Suicide prevention training is offered to students and staff by the Campus Suicide Prevention Program through the REACH program.

More information about suicide-related services is available at suicideprevention.osu.edu. The Franklin County Suicide Prevention Coalition hotline is 614-221-5445.